Still life is one of the most wide-spread, most classical and most known subjects in art. It’s a genre that underwent a very long formative journey in order to become autonomous and regarded as equal to historic compositions. Viewing still life from the very beginnings of Western art to this day, we can follow the development of culture, philosophy and human thought through centuries.

In ancient times, still life was widely spread among the wealthier layer of society that could afford wall paintings. Some examples of the subject were found in Egyptian tombs, but more beautiful examples can be seen in remnants of the great Roman civilization in Pompeii, Herculaneum or Oplontis. The famous ancient Greek fable of painters Zeuxis and Parrhasius tells of their skill-battle in painting of a still life piece. However, after the rise of Christianity and the fall of the Roman Empire in the 4th century AD, this interesting genre was largely forgotten, to re-appear in the early days of Renaissance art as the background support or decoration for the elaborate figurative, religious or mythological scenes.

History of art marks one of the first still life compositions to be “Hare” from 1502 by Albrecht Durer, who was impressed by Italy, although he painted in the Northern style. One of the first paintings that stood as sole still life compositions was definitely “Fruit Basket” by Caravaggio, executed in 1599, at the time when the genre was getting accepted more widely. Still, it wasn’t until the 17th century that the still life subject reached its highpoint in the elaborate, philosophical and masterly works by Dutch and Flemish masters.

Still life genre started flourishing in the Northern Europe as a direct result of the Reformation. Rebelling against the Vatican policies, religious painting in Holland, Flanders and Germany started declining, so a new room was created for other, non-figural types of representation. Although ornate and lavish was rejected, oil painting as a technique was much favored in the northern countries. The political and religious situation allowed for still life to develop further, and become one of the most deeply symbolic types of baroque subjects, filled with references to Christianity, virtues and proper life.

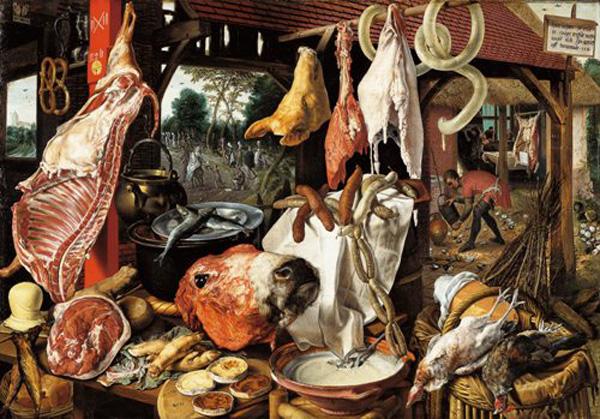

Middle of the 16th century birthed elaborate scenes of shops, depicting highly developed artisanal society of Holland and Flanders. A few of the masters of this time were Pieter Aertsen and Joachim Beuckelaer. A special type of still life emerged a little later. The name for it was “Vanitas” – vanity to be exact, composed with elements specially chosen to remind the observer of his ephemeral nature and to focus his attention to the everlasting brevity of life by stating “Memento Mori” – Remember the Death. The rising population of Dutch Puritans accepted this type of painting happily, as it depicted everything they believed in – serving as propaganda for virtuous, modest life. This was the time of the most famous still life painters we admire today – Harmen Steenwyck, Pieter Claesz, Willem Kalf, or Jan Davidsz de Heem.

In the south, still life was not as popular, as the Counter-Reformation politics was ruling the scene. One of the rare examples is the mentioned Caravaggio piece, or some of the works assigned to the Neapolitan Baroque in the 17th or 18th century. Spanish painter Francisco de Zurbaran did accept the subject, but his renderings of the theme were significantly more dramatic in lighting than the northern elaborate works. The genre will reach its peak a lot later in Spain in the work of Francisco Goya.

In France, however, still life became autonomous and desirable perhaps only with Chardin in the 18th century. Jean-Simeon Chardin took the realistic nature of the genre to a new level, depicting wonderful, almost tangible compositions. He was followed by Theodore Gericault in the 19th century, although still life was not the first choice of this Romantic master.

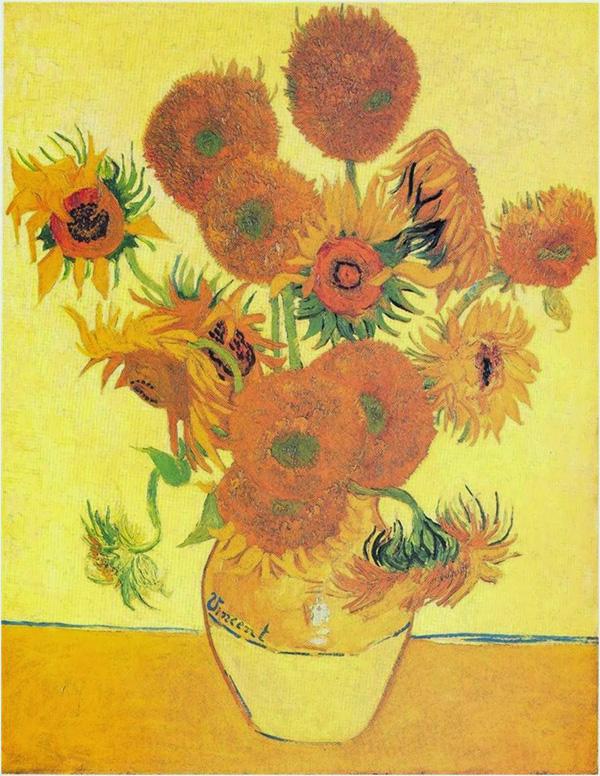

Finally, in the 19th century still life got the complete recognition as the artistic genre, and by the end of the century it was no longer considered lesser among the genres. Henri Jean Theodore Fantin-Latour was particularly famous for his still lives with flowers, but Impressionists are the ones that brought new era to the subject. Paul Cezanne is perhaps one of the most important painters who referred a lot to geometry, thus setting the foundation for Cubist theories, while depicting still lives and St. Victoire landscape. One of the most famous still life series from this period is the one with sunflowers by Vincent Van Gogh.

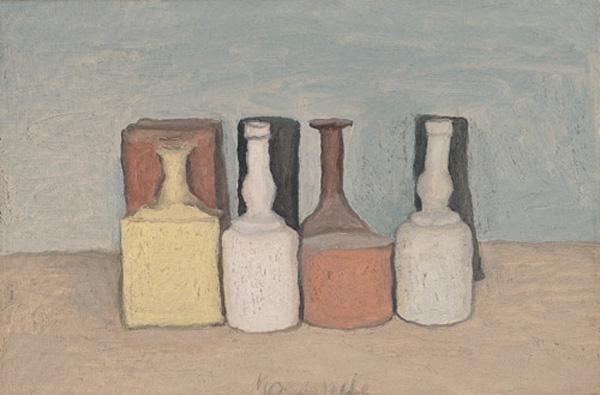

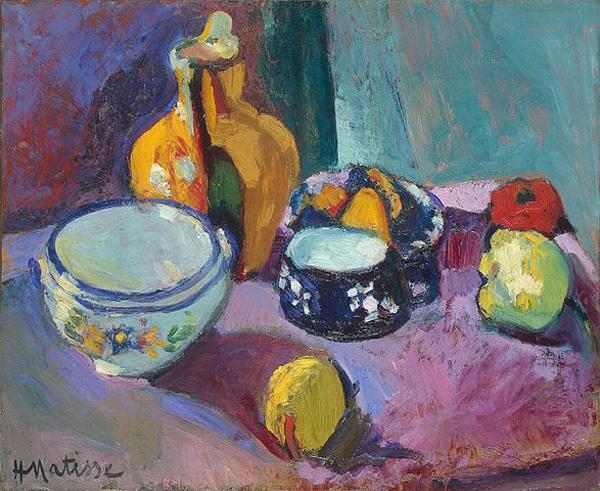

Twentieth century brought major shifts in art, and subsequently in genres as well. Although early modernists did employ still life very much, starting with Fauvists, over German Expressionists, to Cubists, the subject itself was of not much importance. The more important were theories upon which it was painted and styles that were multiplying relatively fast. Still, artist such as Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, Picasso did express themselves through still life compositions. Especially dedicated to the theme was Giorgio Morandi, an Italian painter who portrayed simple objects with unique, lyrical style. After the birth of abstract art, a group of modernists remained faithful to the still life genre, but the importance of the arranged objects will never be the same as in the Baroque era again. One of the most emotional still life compositions of the time is a piece by David Hockney, “Still Life on a Glass Table”, from 1971, depicting this classical and beautiful theme in a completely new manner, while retaining the symbolic nature of the genre.

Still life is definitely one of the most important genres in history of art. It reflects the cultural history, as well as the mastery of every individual artist who painted it, while today it is still one of the most essential themes taught and exercised at various art schools across the globe.